Halal Explained: From Food Fundamentals to Certification

Dr. Mian N. Riaz

The demand for halal food continues to rise steadily—not only in the United States, Canada, and Europe, but also across the Middle East, Southeast Asia, North Africa, and Australia. The halal consumer segment is now one of the fastest growing in the global food trade. According to a recent estimate by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, the world’s Muslim population has reached approximately 1.57 billion, making up about 23% of the total global population of 6.8 billion. More than 60% of Muslims reside in Asia, and roughly 20% live in the Middle East and North Africa. Additionally, over 300 million Muslims are part of minority populations in other regions. Europe is home to about 38.1 million Muslims, while Canada hosts around 1 million—roughly 3.1% of its total population. In the United States, although figures vary, estimates generally place the Muslim population at around 8 million.

Globally, the halal food industry is valued at approximately $635 billion annually. In the United States alone, the halal food market is worth an estimated $17.6 billion, according to the Islamic Food and Nutrition Council of America. Increasingly, non-Muslims are also purchasing halal products due to their reputation for cleanliness, safety, and lower risk of cross-contamination. As a result, the halal food sector represents a significant business opportunity for food companies seeking to serve a diverse and expanding consumer base.

Over the last three decades, numerous halal grocery stores, ethnic markets, and restaurants have emerged, especially in large urban centers. Historically, the mainstream food industry has largely overlooked this demographic, instead directing its focus toward exports to predominantly Muslim countries. Traditionally, Muslim entrepreneurs would perform animal slaughter themselves, and the idea of third-party halal certification was unfamiliar. However, beginning in the late 1990s, small and mid-sized enterprises identified this untapped market and began addressing the growing demand. Today, halal certification is becoming just as common for food sold domestically as it is for exports. Products labeled with halal certification are widely trusted by Muslim consumers and are also appealing to individuals of other faiths, particularly when the certification is issued by a credible authority.

Muslims are permitted to consume all foods that are clean and wholesome, with a few key prohibitions. These include:

As long as manufacturers avoid these sources, halal food processing closely resembles conventional production practices.

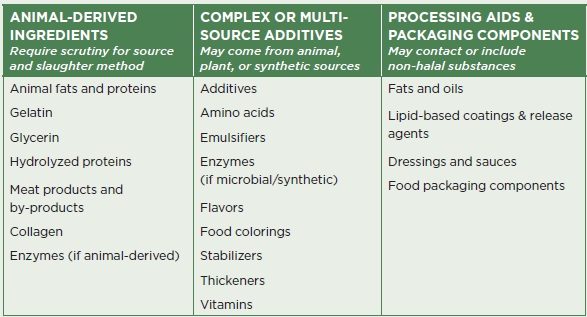

Food manufacturers must pay close attention to certain ingredients and their origins, including additives; amino acids; animal fats and proteins; food colorings; dressings and sauces; emulsifiers; enzymes; fats and oils; lipid-based coatings and release agents; flavors; gelatin; glycerin; hydrolyzed proteins; meat products and by-products; food packaging components; stabilizers; thickeners; vitamins; and whey proteins. To maintain halal integrity, strict measures and precautions must be taken to prevent any form of cross-contamination with non-halal substances.

A halal certificate is an official document granted by an Islamic certifying body, confirming that the products listed comply with Islamic dietary principles. These principles include but are not limited to:

Halal certification generally falls into two main categories, and the length of validity depends on the nature of the product. The first type is a site certification, which verifies that a particular location—such as a manufacturing plant, food processing unit, kitchen, slaughter facility, or food service outlet—has been inspected and meets the standards required for producing halal food. However, it’s important to note that this certificate does not guarantee that all items produced at the site are halal certified. It is not a substitute for individual product certification.

The second type of certificate is product-specific or quantity-specific. This confirms that a particular product—or a designated quantity of it—has been evaluated and approved under halal standards as defined by the certifying authority. These certificates are often issued for a particular batch or shipment meant for a specific distributor or importer. In the case of meat and poultry products, where each consignment requires validation, batch or shipment certificates are commonly issued.

The duration of validity for a halal certificate varies depending on the product. Batch certificates remain valid for the lifespan of that specific lot in the market, typically up to the “best by,” “best before,” or expiration date. When a product is produced using a standardized and approved formulation, certification may be granted for one to three years. As long as the product continues to be manufactured under the agreed process and meets all certification requirements, its halal status remains valid throughout that period.

While any qualified Muslim individual, Islamic institution, or agency can issue a halal certificate, the recognition and acceptance of that certificate ultimately depends on the country of import or the local Muslim population being served. For instance, when exporting food to countries like Malaysia and Indonesia, only certifying bodies listed on the official approval lists of those nations are permitted to issue valid halal certificates. In the U.S., more than 40 organizations offer halal certification; however, only five are currently recognized by Indonesia’s Majelis Ulama Indonesia (MUI), as per the latest available information. Malaysia’s Jabatan Kemajuan Islam Malaysia (JAKIM) recently reduced its list of recognized U.S. certifiers from 16 to just three. According to JAKIM, about half of the delisted organizations were no longer active, while others were removed for not adhering to the required standards.

Therefore, food producers must understand not only halal regulations for specific countries but also which certifying organizations align best with their operational and export goals.

Companies should work with certification agencies that are widely accepted both in their target export markets and among local Muslim consumers.

Currently, Malaysia and Indonesia are the only countries with structured, government-led programs to accredit halal certifiers. Other nations, such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Bahrain, Singapore, the UAE, and Kuwait, may evaluate or approve halal organizations for certain purposes, but not through formalized systems.

“Due to the intricacies of modern manufacturing and widespread use of animal-derived ingredients, virtually any product consumed or applied by Muslims can undergo halal certification.”

This includes items used externally, not just those ingested. While pharmaceutical and medicinal items used for health and wellness are not required to be certified, many informed Muslim consumers still prefer them to meet halal standards whenever possible.

Products that can be halal-certified include:

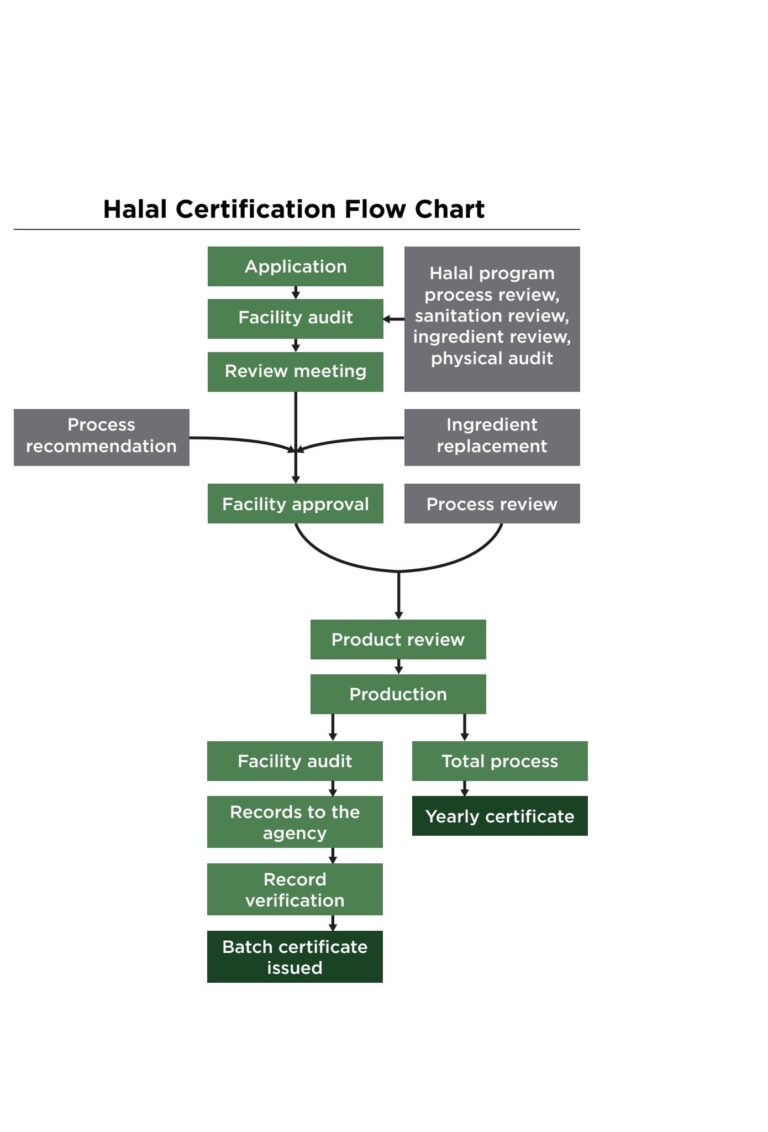

The process of obtaining halal certification begins with selecting a halal certification agency that aligns with your marketing and export objectives. Countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore maintain government-regulated halal certification systems, while nations that primarily export food tend to rely on independent certifying bodies. For exporters targeting specific regions, working with a certifier accepted or officially recognized in that market is advisable. For broader or global distribution, it’s best to partner with a certifier that operates on an international scale.

The initial step involves submitting an application, which details the manufacturing procedures, the specific products requiring certification, the intended sales regions, and complete ingredient information. Once received, the certifying body reviews the submission and typically schedules an audit of the production site. At this point, companies should also confirm and negotiate the associated fees and sign an agreement, as annual certification costs can sometimes reach several thousand U.S. dollars.

During the audit and review of ingredient details, the certifier may require substitutions for any non-compliant materials. A multi-year supervision agreement is usually signed between the certifying body and the manufacturer. Following approval, a halal certificate is issued—either for a single shipment (batch certificate) or for a one-year term, depending on the arrangement.

Overall, halal certification for food products is a structured and manageable process, as represented in the chart below:

Once a product has been halal-certified, it typically features a logo or symbol on the packaging to inform consumers of its compliance. For instance, the Islamic Food and Nutrition Council of America (IFANCA) uses the Crescent-M “☪” symbol to indicate the product is “permissible for Muslims.” Other certifying bodies use variations such as the Arabic letter “ح”, the word “halal” in Arabic script “(حﻼل)”, or simply the English word “halal.” Products are more likely to gain consumer trust when they carry the mark of a well- known local halal authority—or, for imported goods, the logo of a recognized and reputable international certification agency.

With access to a global halal market of over 2.5 billion people, the opportunity for growth is significant. The halal symbol serves as a trustworthy, third-party validation for consumers seeking religious compliance. Importantly, it broadens market reach without alienating non-Muslim customers. Halal certification improves a product’s appeal in Muslim-majority countries and communities and requires only a modest investment—especially when compared to the potential return in sales and revenue. In short, halal certification strengthens a product’s reputation and positions it to meet diverse consumer expectations.

Dr. Mian N. Riaz is the Associate Department Head and IFANCA Professor in Food Diversity in the Department of Food Science and Technology at Texas A&M University. He joined Texas A&M University 32 years ago after completing his Ph.D. in Food Science. Dr. Riaz has published seven books. His first book, “Halal Food Production,” is widely used in universities for Food Science and Nutrition majors and has been translated into Chinese, Persian, and Korean. He has received several prestigious awards from various institutions.